When we left off in our Star Trek saga, I had just driven my gold Chrysler Sebring Convertible with the black ragtop through the front gates of Paramount Pictures in Hollywood, there to enter the world of network television for the first time. And now we begin the tale of what awaited me there.

That experience of driving through the front gates of Paramount like Norma Desmond with Max in Sunset Boulevard (which you’ll remember I had seen on Broadway just a couple of days earlier) and parking in the main studio parking lot proved to be a one-time thing. For the rest of my stay, I had a parking permit at the facility on, I believe, Gower Street across from the studio, and I entered through the Lucille Ball Building. As a matter of history, all Trekkers and Zonies (Twilight Zone devotees) owe a debt to Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. It’s true. The de facto original pilot for The Twilight Zone was a Rod Serling play called “The Time Element” starring William Bendix (The Life of Riley) which was produced for The Desilu Playhouse. This was what interested CBS in Rod’s pitch for a fantasy anthology program. And anyone who’s watched the closing titles of the 1960s Star Trek knows that Desilu Studios was the original owner of the Star Trek franchise. Lucy herself was known to have been very proud of Trek, and it was she who sold the franchise and all of Desilu’s other holdings to Paramount.

But I digress. Just a few steps inside the studio lot from the Lucy Building was the Hart Building, where the writing and production staff for the Star Trek TV series was housed. That was where I would be spending most of my time. Immediately across the lot was the Gary Cooper Building, where other producers including one who was of particular interest to me worked, and where some of the larger production meetings were held. We’ll get to that in due time. Down the way was the studio commissary, and on the opposite end of the lot were other offices including payroll and Human Resources, and I assume other exectutive-type offices. Also on the far end was the Star Trek Art Department, where I had a very nice visit with the Okudas, Michael and Denise (we’ll talk about them and that visit in due time) and illustrator John Eaves (him too). The far end was also where the Star Trek sets were located, as well as the trailers in which the stars of the shows relaxed when they weren’t shooting.

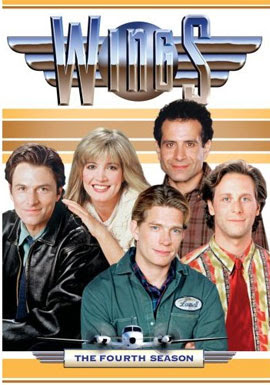

A perusal of the studio lot would also take you to places like the back lot where they shoot a lot of exterior city scenes, an office building that is sometimes used as the exterior facade for various places of interest (such as, I believe, the high school in Grease--or was it Happy Days?), and a theatre/cinema where previews of new films are sometimes screened. Basically, on any given day at any given time at Paramount Pictures one is liable to run across someone or something of interest. While I was there, the airplane that the Hackett brothers flew in the sitcom Wings was being kept right out in the open in a little alcove next to the Hart Building. (And we’re going to have a story about my encounter with one of those Hackett brothers shortly.) I walked by it and touched it every day. A couple of times I was out on the grounds when Moose, the little dog who played Eddie on Frasier, was being walked by his handler. Every time I watch an episode of Frasier now I remember the times I got to pet little Eddie! (Moose passed away a couple of years ago.)

However, on to the experience of being inside Star Trek itself. I occupied the Interns’ Office on the top floor of the building, where I had the place to myself for about half of the six weeks I was there. They didn’t have a Deep Space Nine intern when I arrived and it took them a little while to get one. Eventually I was joined by a woman named Jennifer, who had been working as a grip and as the person who tapes the microphones to performers on soundstages. (One of the people she had miked was Whoopi Goldberg, as I recall.) Jennifer and I got on fine; one day I brought in one of my sketchbooks, full of character designs and studies of hot-looking guys, to entertain her. I would give her little mini-lessons in Star Trek lore and we would compare story ideas and she’d tell me about some of her Hollywood experiences and some of the people with whom she’d worked. She had a crush on TV star Peter Onorati, who had starred in the drama series Civil Wars by Steven Bochco, among other things. (On The Outer Limits he was Fred Savage’s father in the episode “Last Supper.” Desperate Housewives fans know him as Warren Schilling, the wife-beating nightclub owner from this past season’s episodes.) So one fine day as I’m on Gower Street on my way to the parking facility, who should drive by in his SUV but...yep, Peter Onorati. I called out to him and we exchanged waves. (We’re going to talk about what to do when you meet a movie or TV star shortly. I encountered a number of them, as you can surmise.)

So what does a Screenwriting Intern at a TV series do? The position is essentially that of a paid observer. They’re hoping to recruit writing talent, and the idea is that the intern will observe everything pertinent about how a TV series is written and produced, listen and learn, and prepare to pitch his own story ideas. If all goes well, the producers will at least buy an idea to be developed into a story, and that will give the intern a foot in the door to pitch more ideas and perhaps even work on a script. Star Trek was keenly interested in developing talent for its writing staff; the Holy Grail for an intern was to be invited to join the staff full time. One of the Voyager Executive Producers, Brannon Braga, had started out as an intern on Star Trek: The Next Generation, so it was not impossible. A TV producer, you should be intrigued to know, is basically a writer with power. TV producers start out as writers. Something else you should know: The next time you’re watching a scripted TV series, look at the credits. You see all those Story Editors and Executive Story Editors and Story Consultants and Executive Consultants and so forth? You know who all those people really are? They’re writers. All those fancy job titles that TV series and TV production companies dream up are actually ways to get more writers onto the payroll. All those people, and the people who are actually credited as producers, are responsible for writing the show! It’s true. They do other things too; they actually do have executive decision making powers, and they do supervise people who perform other functions for the show. But trust me: They’re writers, every man and woman Jack of them. TV is run by writers.

So, as an intern, one sits in on a lot of meetings where writers with power make decisions about the show and supervise other people who work on the show. I spent lots of time in the office of one Ms. Jeri Taylor, the Executive Producer who had the most hands-on responsibility for producing Voyager. (It was originally the office of Gene Roddenberry himself, a fact I was to learn from Jeri my last day there. I’m sort of glad I didn’t know where I was sitting until the end. I think I would have been awestruck if I’d known that going in.) Jeri Taylor was the wife of the man who produced the whodunit series Murder, She Wrote starring Angela Lansbury--a fact that properly amused my mother, who has read every word that Agatha Christie ever wrote and was a great fan of that show. I should take this opportunity to tell you a story about Jeri and how she got to be where she was. Jeri Taylor is a woman who came into Star Trek when she was in her 50s, with no background whatsoever in science or in science fiction. She had worked in television since her 30s, writing, producing, and directing crime and murder shows including Quincy starring Jack Klugman and Jake and the Fatman starring William Conrad. (This latter also starred Alan Campbell; remember him from the performance of Sunset Boulevard that I attended?) Somehow she had gotten herself invited to pitch and write for Star Trek: The Next Generation--with no knowledge whatsoever of Trek and with the belief that Trek was in fact a children’s show! What she did to prepare is something that I must warn you never, ever to attempt.

This woman in her 50s got herself videos of the entire 1960s TV series, all of the films that had been produced up to that point, and probably half of Next Generation, as well as the books The Making of Star Trek and The World of Star Trek--and she crammed them like a college student who’d postponed studying for an exam! She crammed the history, universe, characters, and stories of Star Trek. I don’t know in how short a time she learned the entire series, but it was a crash course with an emphasis on the “crashing”. You know how inadvisable I consider this? It’s something I would never attempt; that’s how inadvisable it is! It’s the ultimate in “Don’t Try This At Home!” EVER! By rights, Jeri Taylor should not have been producing Star Trek Voyager. She should have been off in a corner somewhere, in a condition like that in which Phoenix left Mastermind in The X-Men #134. (Look it up.) I’m telling you, if you’re new to Star Trek, regardless of your age, don’t ever do this!

But Jeri Taylor, bless her heart, did it, and she survived, and she became an Executive Producer on Next Generation and an Executive Producer and co-creator of Voyager, and after Rick Berman, the producer to whom Gene himself gave the reins of the Trek universe, Jeri was the person in charge. Her producing posse also included the aforementioned Brannon Braga, another Executive Producer; producers Joe Menosky and Kenneth Biller; and Story Editor Lisa Klink, the person who had invited me aboard. So there I was, in the office of the Great Bird of the Galaxy himself, attending meetings with the people responsible for the odyssey of the Starship Voyager through the unknown Delta Quadrant of the galaxy. And what adventures lay in store for me there, and in Hollywood at large? That will be the subject of the next chapter of our Star Trek odyssey.

TO BE CONTINUED.

No comments:

Post a Comment

COMMENT ON THIS POST.